Germany’s colonial past has been, if not forgotten, certainly a less-explored aspect of the history of European incursion and exploitation of Africa’s peoples and resources. But this book goes a long way in correcting this oversight. The author, Henning Melber, born in 1950, is the son of German immigrants who settled in Namibia in 1967. He later joined SWAPO, the Namibian liberation movement, and has since become one of the most respected academics on Germany’s “colonial brand”.

Melber posits that the recent invigoration of debate on Germany’s colonial past has been hindered by amnesia, denialism and ignorance among the German population as a whole. His book is a “modest effort” to combat this.

He suggests that Germany’s colonial history in Africa has often been overshadowed by the horrors of the Holocaust. But Melber also points out that many senior Nazis had colonial careers. He writes: “A colonial mentality remained an intrinsic part of the Weimar Republic and the Nazi era.” A study of Germany’s colonial rule in Africa can thus provide new perspectives on Nazism, German racial thinking and colonisation.

Roots of genocide

The book traces the period from the mid 1800s when Germany actively sought to expand its global reach, control and trading potential. In 1862, the Brandenburg African Company established the small trading post of Great Friedrichsburg on the coast of what is today Ghana.

“By the turn of the 20th century,” Melber informs us, “Imperial Germany had become one of the biggest colonial empires in terms of foreign territory, euphemistically dubbed ‘acquisitions’.”

It was in South West Africa – later Namibia – that German colonialism has left perhaps its darkest legacy. Adolf Lüderitz from Bremen eyed up a coastal area along the Atlantic littoral to develop the bay that the Portuguese called Angra Pequena – later called Lüderitz Bay. Its occupants would benefit not only from the rich guano deposits on the small islands in the vicinity, but also its potential as an entrepôt for the trades in copper, ostrich feathers, cattle and guns.

Lüderitz petitioned the German government, and the German flag was hoisted in the bay for the first time in 1884, to declare German South West Africa. But it was not until 1893 that an official German administration was established in the largely unprofitable colony.

From the outset, Melber shows, the German colonists showed scant regard for the rights of the indigenous peoples. Leaders who resisted were coerced into “protection treaties” by force of arms, or were executed. By the mid 1890s an influx of settlers were appropriating land and livestock by violent and fraudulent practices.

The local Ovaherero community retained a large extent of control and economic influence, which was only brought to an end as the result of a devastating cattle-plague outbreak in 1896-97. The immense loss of cattle made them more vulnerable and reliant on traders, land exchange and their labour. By the turn of the century, the economy “was more and under settler-colonial dominance”.

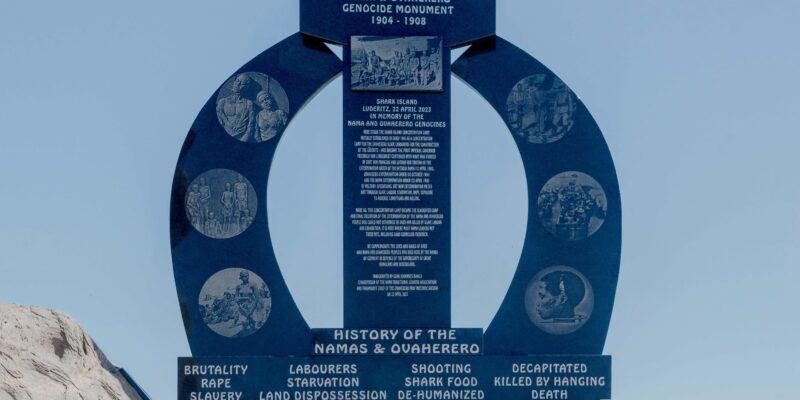

The inevitable resulting rebellion was brutally suppressed by mass killings and “unlimited force of arms”. Rebellious Nama and Ovaherero peoples who resisted German occupation were sent to concentration camps and used as forced labour, resulting in horrific death rates. The period of 1904-1908 has been characterised by many scholars as genocide – the first of the 20th century. Estimates suggest between 24,000 and 100,000 Ovahereros and 10,000 Nama were killed, with thousands driven into the desert to die of dehydration.

As Melber comments: “If there are any keywords to characterise the main effects of German colonial rule for the indigenous people, these would include land fraud, genocide, contract labour and apartheid.”

Violence and rebellion

Violence was also central to Germany’s attempts to take control of Cameroon. The Hamburg Chamber of Commerce endorsed an initiative by Adolph Woerman to annex the Camerrioon coast, allowing traders to avoid the tax imposed by French and British colonial powers. It would, it was hoped, develop routes to the interior.

In 1884, a German flag was hoisted with the support of some local Duala kings – who nevertheless insisted on “continued ownership of the land and recognition of the local chiefs as rulers of the Cameroons”. That turned out to be wishful thinking, Melber writes.

The resulting disagreements sparked conflict and “pacification” measures by the Germans. By 1889 a direct form of German colonial administration was established. Land appropriation and forced labour were soon features of the administration, which in 1891 recruited a mercenary unit of Dahomey slaves to carry out particularly brutal acts of violence and atrocities. But the colony was never truly pacified – military administration lasted until the end of German rule in half of the proclaimed territory.

Indeed, Melber references the many Africans who, with extraordinary bravery, stood up to challenge the white usurpers.

He highlights the son of King Dika Akwa, Prince Mpondo Akwa. Schooled in Germany, the prince was soon considered a thorn in the side of the authorities. In 1902 he was quoted as stating that indigenous peoples would refuse “to be deprived of their black culture, law and habits, which had existed long before the encounter with whites”.

He returned to Cameroon and in June 1911 was jailed for making “German-phobic remarks”. In 1914 he was extra-judicially executed. However, as Melber writes, the Germans were ultimately “unable to reap the fruits of the seeds of terror they had sown”. A joint British and French invasion of the colony, lasting from September 1914 to January 1916, brought an end to the bloody German presence, but not to the benefit of the local populations.

“Cameroon was shared and divided as prey between the British and French… which sowed new seeds of chronic internal conflict and violence,” Melber writes.

An East African famine

German colonial rule in Tanganyika, East Africa, was driven by German citizen Carl Peters, motivated, according to Melber, by “an imperialist nationalism, combined with social Darwinism”. The German East Africa Company was formed, and the Berlin Conference created German zones of influence which by 1886 included present day Tanzania, Rwanda and Burundi, German East Africa ultimately became Germany’s largest colony.

As in South West Africa, Peters – who Melber describes as “a megalomaniac convinced that ruthless violence was the only language the locals understand” – resorted to open violence to confront a combined Swahili and Arab uprising.

Colonists attempted to establish a plantation economy based on sisal, coffee, rubber and cotton cultivation – but labour was a perennial problem owing to violent and unhealthy conditions. Hermann Wissmann was appointed as commissioner for East Africa and arrived in Zanzibar at the end of March 1889. He resorted to massacres to suppress the rebellious, employing mercenaries mainly of Sudanese, Somali and Zulu backgrounds.

By the mid 1890s, rebellion was commonplace across the colony. The Maji Maji rebellion was brutally crushed – potentially with the loss of up to 300,000 lives as famine spiked.

Changing blindness to the past

In the light of the bloody legacies in Namibia, Cameroon, East Africa and beyond, Germany must “walk the walk” of reconciliation, Melber writes. “This includes paying more adequate domestic attention to the crimes committed in the name of German ‘civilisation’ abroad by dealing with these skeletons in the closet in as strict a way as with the later Nazi mass extermination at home.”

He delves into the issue of reparations; the return of artefacts; and the dominant narratives towards the colonial past in Germany today. Most important, he concludes, is that the government should foster public awareness and enlightened education in order for recent efforts to rise above “mere political symbols”.

To quote the book’s opening lines: “we cannot change the past, but we can change our blindness to the past.”

The Long Shadow of German Colonialism: Amnesia, Denialism and Revisionism

By Henning Melber

£30 Hurst Publishing

ISBN: 9781805260455

Comments