Air quality has become one of the most important public health issues in Africa. Poor air quality kills more people globally every year than HIV, TB and malaria combined. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Air pollution makes people less productive because they get headaches and feel tired.

Air quality has become one of the most important public health issues in Africa. Poor air quality kills more people globally every year than HIV, TB and malaria combined. And that’s just the tip of the iceberg. Air pollution makes people less productive because they get headaches and feel tired.

India, for example, has poor air quality. The impact of India’s poor air quality on its GDP is about US$100-billion every year.

The health risks of poor air quality are known. But it’s always been costly to set up monitoring stations to measure it regularly.

When measuring air quality, the goal is to identify the hotspots, not just the average air quality in the city

I am a particle physicist, and the director of the Institute for Collider Particle Physics at the University of the Witwatersrand and the iThemba Laboratories for Accelerator Based Sciences, a unit of South Africa’s National Research Foundation. As part of our technology transfer activities, we launched the South African Consortium of Air Quality Monitoring, a multidisciplinary team of scientists with strong connections with policy makers and who are interested in improving air quality in South Africa.

We decided to create, for the first time in South Africa, a cost-effective air-quality monitoring system based on sensors, internet of things and artificial intelligence. We have named this system Ai_r.

Our team of 25 people includes more than 20 years of experience as particle physicists in working with sensors, communications and AI. In particle physics, we create complex systems with different technologies and different disciplines. Particle physics includes electrical and information engineering, data science and AI, among others.

Using AI

There are only 130 big air-quality measuring stations in South Africa. They only measure the air quality in the vicinity of the station. This is why we need cost-effective, dense networks made up of Ai_r systems set up all around these stations, to measure air quality in a much wider area.

Our vision is to place tens of thousands of these devices all over South Africa.

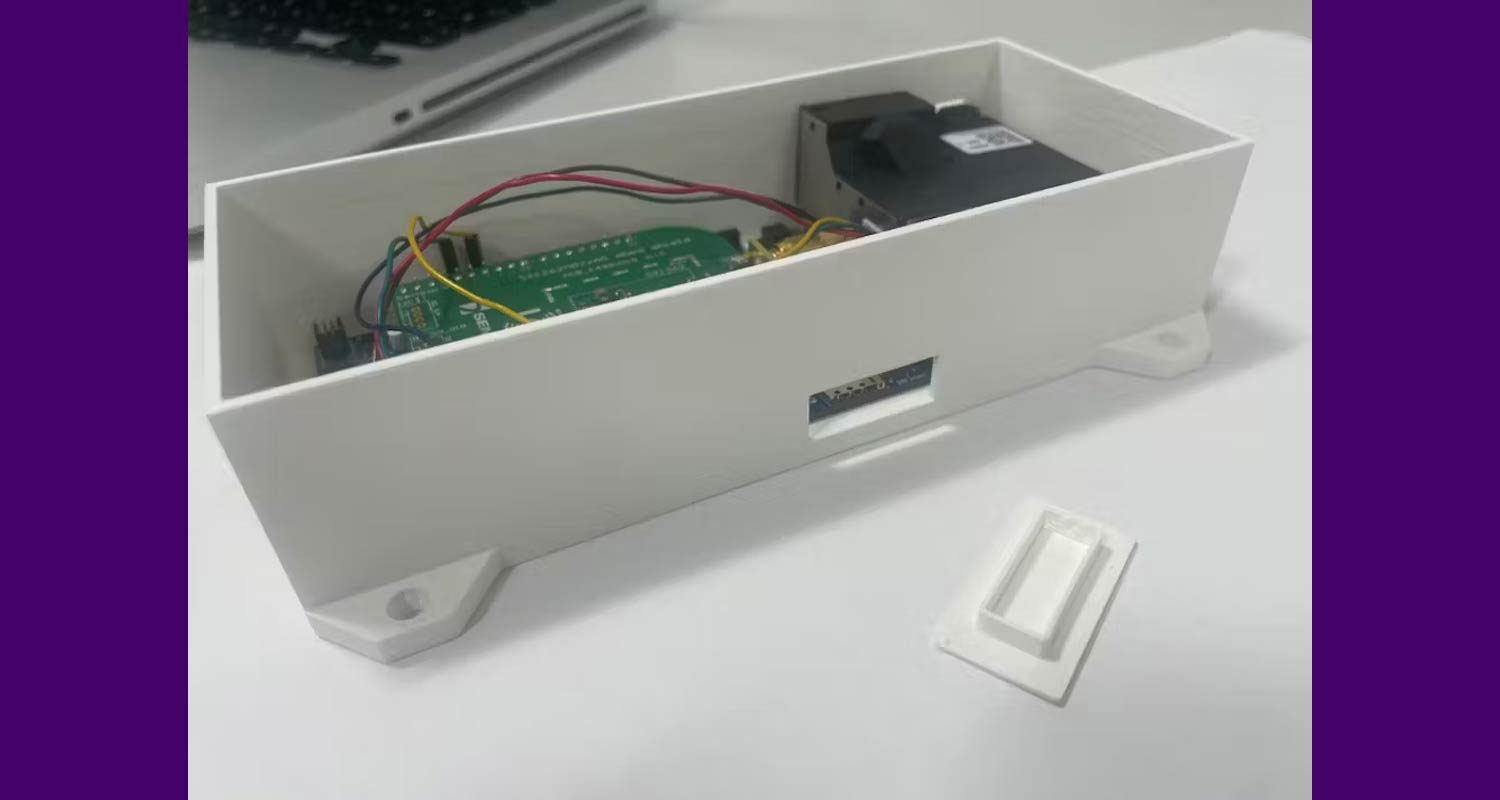

Ai_r is made up of a collection of small boxes that cost about R1 800 to make. The boxes can be mounted on a windowsill of any building, where they take air samples and feed this data back to a cloud in real time. Modelling and forecasts are made with AI coupled to the cloud.

Read: Eskom’s pollution disaster laid bare

AI does not do magic. It is a bunch of mathematical tools that scientists control to perform a task. It integrates sets of data, learns from the data and creates automatic models. That saves a tremendous amount of resources.

In air quality monitoring, AI will learn from the vast wealth of data that these sensors will produce and then make predictions. For example, Ai_r will be able to tell us the impact of weather changes on air quality so that we know which areas will have more polluted air.

Without AI, it would be very difficult to come up with a cost-effective system that could monitor air quality and give us predictions.

When measuring air quality, the goal is to identify the hotspots (where air quality is worst), not just the average air quality in the city.

When measuring air quality, the goal is to identify the hotspots (where air quality is worst), not just the average air quality in the city.

A hotspot of very polluted air can be situated quite close to a cold spot where the air quality is better. For public health reasons, we need to know and be able to forecast where the air quality will be bad on any given day. This is the only way we will be able to convince the authorities to set up ways to curb air pollution in badly affected areas.

We have already rolled out about 20 of the new devices in Soweto and Braamfontein in Johannesburg, and 120 more are coming in the next months. Both parts of the city have tens of thousands of vehicles driving through every day, putting them at high risk of air pollution.

In cases of power cuts, the devices have cost-effective batteries that last for days. They are very easy to maintain

We have also placed air-quality sensors at the University of the Witwatersrand and iThemba Labs. We have an agreement with the Gauteng department of education to deploy these at schools in the Soweto area. Hospitals in the private Netcare group have also agreed to host the air-quality devices.

There is a public dashboard on our website where you can see all the data we gather.

The project was launched in June 2024. The government has reacted positively and we are now integrating the system into the official South African system of air-quality scores, SAAQIS. We also encounter strong support by the City of Johannesburg to deploy further.

The Ai_r system measures particulate matter 2.5. These are extremely tiny particles of polluting matter such as dust, dirt, soot or smoke. The problem with these particulates is that people inhale them. They get into people’s bloodstreams and can cause heart attacks, cancer and other diseases. This is why the amount of particulate matter 2.5 is typically used as a benchmark for air quality globally.

How it works

The air-quality device is housed in a box. It has a small laser that shoots light onto air. Depending on how that light scatters and reflects, you can measure the concentration of particulates. Then the measurements are sent to the tiny computer inside the box which communicates through an antenna every five minutes, through IoT technologies, to a cloud-based system where the data is stored. So nobody has to be there collecting air quality samples anymore.

We have also optimised the devices so that they use very little electricity. In cases of power cuts, the devices have cost-effective batteries that last for days. They are very easy to maintain. They are affordable to roll out across South Africa.

The Ai_r device measures air pollution. Image: SACAQM

The Ai_r device measures air pollution. Image: SACAQM

The existing network will keep growing to become, towards the end of 2024, the largest cost-effective, automated air-quality measurement system in Africa.

We really need to measure pollution and find out just how bad it is so that mitigating strategies can be designed that target problem areas very efficiently. The goal is to improve air quality for people who are most affected by air pollution.![]()

- The author, Bruce Mellado, is professor of physics, University of the Witwatersrand

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence

Comments