The world is witnessing enormous growth in electric vehicles (EV), one of the major green tech interventions aimed at addressing the climate change crisis. EVs are intended to replace fossil fuel-dependent internal combustion engine vehicles, which reportedly emit about 15% of global greenhouse gases.

About 14% (over 10-million units) of cars sold around the world in 2022 were EVs, a five-percentage point increase from 9% in 2021. It is expected that the share of electric cars in global sales will reach 18%, which translates to about 14-million units.

The EV market is projected to maintain its strong growth trend through 2030 and reach almost $1-trillion. As such, this is a new industry that will make a considerable contribution to the global economy and presents significant opportunities for countries and regions positioning themselves to take advantage of the transition to renewable and clean-energy technologies.

The emergence of the EV industry also presents significant economic and environmental opportunities for African countries. Fuel-based vehicles not only worsen air pollution in African cities but also create fiscal pressure on African governments, which have to subsidise fuel costs at about 1.4% of GDP on average. This diverts significant resources away from other urgent needs.

The transition to EVs would therefore go a long way to reducing air pollution and creating fiscal space for governments to attend to other developmental needs.

The African EV market is still small and characterised by slow adoption. For example SA, one of Africa’s biggest EV markets, has only 6,000 EVs on its roads out of a total of 12-million vehicles, while Kenya has 350 EVs of a total fleet of 2.2-million.

However, with the right policies, African countries can tap into the lucrative global value chain of the EV industry. Opportunities abound in the production of lithium-ion batteries that power the electric cars. The minerals used to make these batteries are available in significant quantities in several African countries.

Mozambique has significant deposits of graphite, in Zimbabwe there is lithium, SA boasts manganese, nickel and platinum, while the Democratic Republic of Congo has the biggest reserves of cobalt in the world.

However, African countries have thus far been confined to the upstream and least lucrative part of lithium-ion battery production, which involves the extraction of raw minerals from the ground. The more lucrative downstream stages of production such as smelting and refining , cell production and assembly, happen in countries outside Africa.

While SA does have some manganese refining capacity, the country still exports about 80% of this critical mineral in its raw state. The capacity for lithium-ion battery production, which involves electrode preparation, cell assembly and battery electrochemistry, is simply nonexistent in Africa. Thus, the African economy loses a great deal in potential jobs and foreign currency revenues.

African countries that possess the critical minerals used to make lithium-ion batteries are faced with the challenge of convincing and incentivising mining companies to build smelting and refinery plants, which add value to the minerals before they are exported.

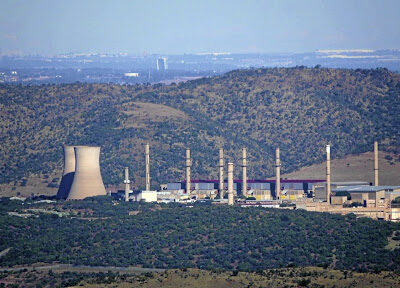

Challenges such as the shortage of skilled labour, lack of proper infrastructure – especially electricity, lack of finance, and unfavourable regulatory frameworks mitigate against African countries’ transition to downstream parts of the lithium-ion battery value chain.

Encouragingly, efforts are under way in some countries to move up the value chain. SA companies such as Manganese Metal Company and Thakadu Battery Materials are producing chemicals needed for cell production, such as manganese electrolyte and nickel sulphate respectively. Mozambique and Tanzania have negotiated with mining companies they host to build more graphite processing capacity in their countries.

In Zimbabwe, which holds significant lithium deposits, a Chinese company recently built a lithium concentrator with capacity to produce 450,000 metric tons of lithium concentrates.

Beyond battery production, African countries also confront the challenge of promoting the adoption of EVs to expand the EV industry in their countries. As has been stated, EVs are yet to make significant headway in the continent’s automobile market, which is still dominated by internal combustion engine vehicles.

Many countries across the continent are developing electric mobility policies to stimulate demand for EVs and encourage their production. Rwanda has adopted several policy measures, including reducing electricity tariffs for EVs, scrapping import duties, and rent-free land for charging stations.

Mauritius’s reduction of excise duties on EVs saw a significant increase in their uptake. However, the development of the EV market would require huge investment in power supply infrastructure. The majority of African countries do not have stable power supply systems, on which EVs depend to run.

Investment in EVs will be capital-intensive, but capital is expensive in Africa due to the perceived high-risk environment. Nonetheless, the global trend towards EVs is irreversible. African governments and policymakers must act quickly to ensure that the continent is not left behind in the transition to EVs.

Monyae is director of the Centre for Africa-China Studies at the University of Johannesburg.

Comments