The successful launch on Christmas Day of the James Webb Space Telescope offers unprecedented new opportunities for astronomers. It’s also a timely opportunity to reflect on what previous generations of telescopes have shown us.

The successful launch on Christmas Day of the James Webb Space Telescope offers unprecedented new opportunities for astronomers. It’s also a timely opportunity to reflect on what previous generations of telescopes have shown us.

Astronomers rarely use their telescopes to simply take pictures. The pictures in astrophysics are usually generated by a process of scientific inference and imagination, sometimes visualised in artist’s impressions of what the data suggests.

Choosing just a handful of images was not easy. I limited my selection to images produced by publicly funded telescopes, and which reveal some interesting science. I tried to avoid very popular images which have already been viewed widely.

The selection below is a personal one and I’m sure many readers could advocate for different choices. Feel free to share them in the comments.

1. Jupiter’s poles

This image is sometimes called ‘Jupiter Blues’. Enhanced image by Gerald Eichstädt and Sean Doran (CC BY-NC-SA) based on images provided by Nasa/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS

This image is sometimes called ‘Jupiter Blues’. Enhanced image by Gerald Eichstädt and Sean Doran (CC BY-NC-SA) based on images provided by Nasa/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS

The first image I’ve chosen was produced by Nasa’s Juno mission, which is currently orbiting Jupiter. The image was taken in October 2017 when the spacecraft was 18 906km away from the tops of Jupiter’s clouds. It captures a cloud system in the planet’s northern hemisphere, and represents our first view of Jupiter’s poles (the north pole).

The images this picture is based on reveal complex flow patterns, akin to cyclones in Earth’s atmosphere, and striking effects caused by the variety of clouds at different altitudes, sometimes casting shadows on layers of clouds below.

I chose this image for its beauty as well as the surprise it produced: the parts of the planet near its north pole look very different to the parts we had previously seen closer to the equator. By looking down on the poles of Jupiter, Juno showed us a different view of a familiar planet.

2. The Eagle nebula

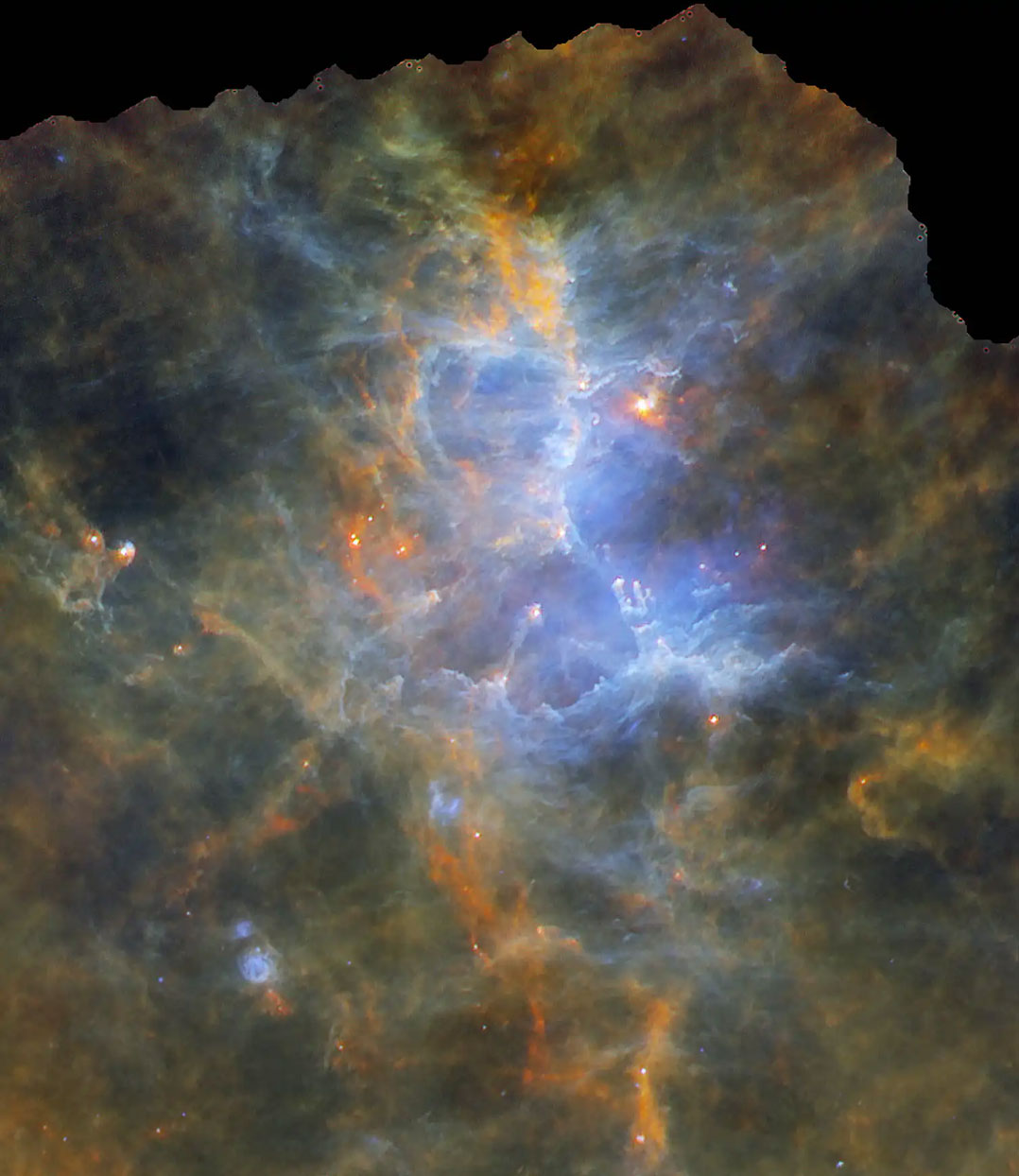

This image allows us to see into the dense, dusty regions of space where star formation takes place. G Li Causi, IAPS/INAF, Italy, CC BY

This image allows us to see into the dense, dusty regions of space where star formation takes place. G Li Causi, IAPS/INAF, Italy, CC BY

Astronomers can obtain unique information by building telescopes which are sensitive to light of “colours” beyond those our eyes can see. The familiar rainbow of colours is only a tiny fraction of what physicists call the electromagnetic spectrum.

Beyond red is the infrared, which carries less energy than optical light. An infrared camera can see objects too cool to be detectable by the human eye. In space, it can also see through dust, which otherwise completely obscures our view.

The James Webb Space Telescope is the largest infrared observatory ever launched. Until its launch, the European Space Agency’s Herschel Space Observatory had been the largest. The next image I’ve chosen is Herschel view of star formation in the Eagle Nebula, also known as M16.

A nebula is a cloud of gas in space. The Eagle Nebula is 6 500 light years away from Earth, which is quite close by astronomical standards. This nebula is a site of vigorous star formation.

A close-up view of a feature near the centre of this image has been called the “Pillars of Creation”. Appearing a bit like a thumb and forefinger pointing upwards and slightly to the left, these pillars protrude into a cavity in a giant cloud of molecular gas and dust. The cavity is being swept out by winds emanating from energetic new stars which have recently formed deeper within the cloud.

3. The galactic centre

Can you spot the Quintuplet cluster and the Arches? Hubble: Nasa, ESA, and QD Wang (University of Massachusetts, Amherst); Spitzer: Nasa, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and S Stolovy (Spitzer Science Center/Caltech)

Can you spot the Quintuplet cluster and the Arches? Hubble: Nasa, ESA, and QD Wang (University of Massachusetts, Amherst); Spitzer: Nasa, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and S Stolovy (Spitzer Science Center/Caltech)

This image looks deeper into space to the centre of our Milky Way Galaxy. It also uses infrared light, this time combining data from two Nasa telescopes, Hubble and Spitzer.

The bright white region in the lower right of the image is the very centre of our galaxy. It contains a massive black hole called Sagittarius A*, a cluster of stars and the remains of a massive star which exploded as a supernova about 10 000 years ago.

Other star clusters are visible too. There’s the Quintuplet cluster in the lower left of the image within a bubble where the stars’ winds have cleared the local gas and dust. In the upper left there’s a cluster called the Arches, which was named for the illuminated arcs of gas which extend above it and out of the image. These two clusters include some of the most massive stars known.

4. Abell 370

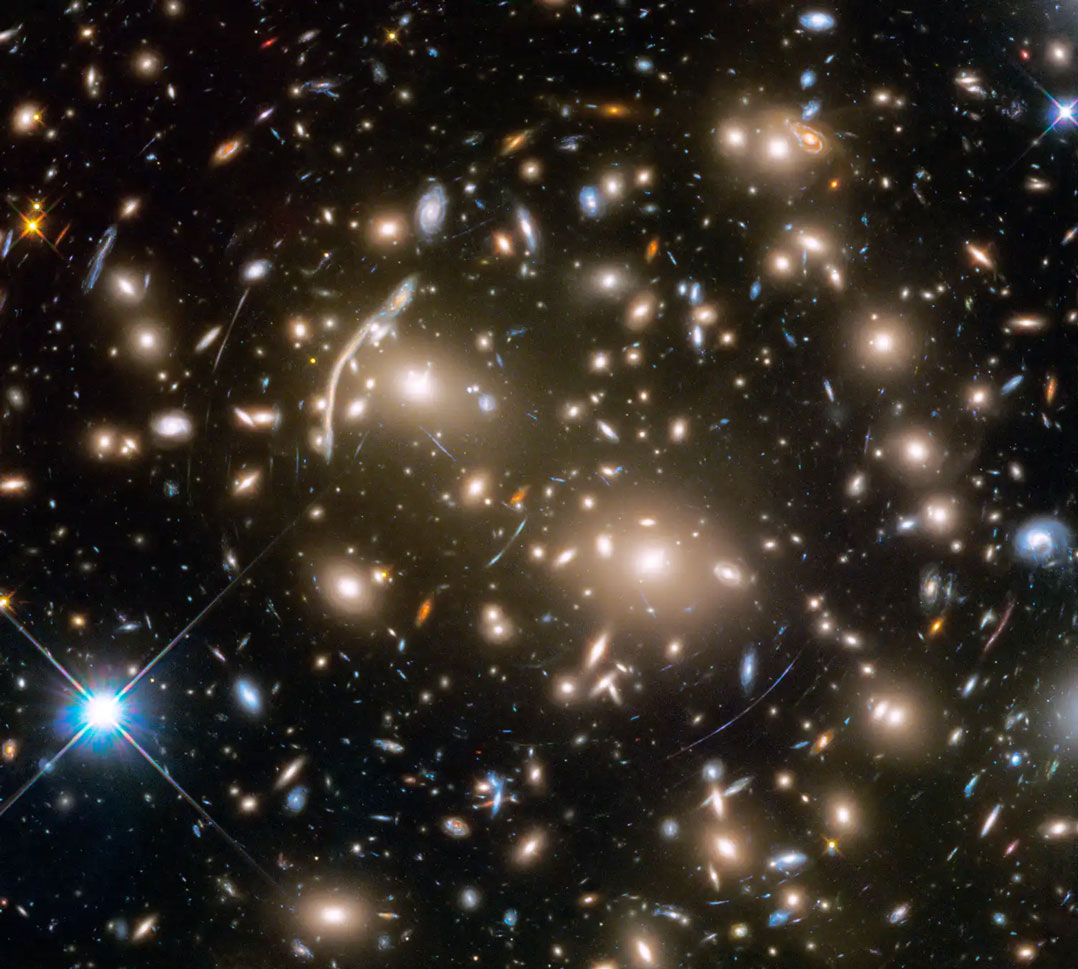

Abell 370 is a cluster of hundreds of galaxies about five billion light years away from Earth. Nasa, ESA and J Lotz and the HFF Team (STScI)

Abell 370 is a cluster of hundreds of galaxies about five billion light years away from Earth. Nasa, ESA and J Lotz and the HFF Team (STScI)

On much larger scales than individual galaxies, the universe is structured as a web of filaments (long connected strands) of dark matter. Some of the most dramatic visible objects are clusters of galaxies which form at the intersection of filaments.

If we look at galaxy clusters nearby (relatively speaking, of course), we can see dramatic proof that Einstein was right when he asserted that mass curves space. One of the prettiest examples which reveals this warping of space can be seen in Hubble’s image of Abell 370, released in 2017.

Abell 370 is a cluster of hundreds of galaxies about five billion light years away from us. In the picture you can see elongated arcs of light. These are the magnified and distorted images of far more distant galaxies. The mass of the cluster distorts spacetime and bends the light from the more distant objects, magnifying them and in some cases creating multiple images of the same distant galaxy. This phenomenon is called gravitational lensing, because the warped spacetime acts like an optical lens.

The most prominent of these magnified images is the thickest bright arc above and to the left of the centre of the picture. Called “the Dragon”, this arc consists of two images of the same distant galaxy at its head and tail. Overlapping images of several other distant galaxies comprise the arc of the dragon’s body.

These gravitationally magnified images are useful to astronomers, because the magnification reveals more detail of the distant lensed object than would otherwise be seen. In this case the lensed galaxy’s population of stars can be examined in detail.

5. The Hubble Ultra Deep Field

Sometimes, less is more. Nasa, ESA, and S Beckwith (STScI) and the HUDF Team, CC BY

Sometimes, less is more. Nasa, ESA, and S Beckwith (STScI) and the HUDF Team, CC BY

In an inspired idea, astronomers decided to point Hubble at a blank patch of sky for several days to discover what extremely distant objects might be seen at the edge of the observable universe.

The Hubble Ultra Deep Field contains nearly 10 000 objects, almost all of which are very distant galaxies. The light from some of these galaxies has been travelling for over 13 billion years, since the universe was only about half a billion years old.

Some of these objects are among the oldest and most distant known. Here we’re seeing light from ancient stars whose local contemporaries have long since been extinguished.

The oldest galaxies formed during the epoch of reionisation, when the tenuous gas in the universe first became bathed in starlight which was capable of separating electrons from hydrogen. This was the last major change in properties of the universe as a whole.

The fact that light carries so much information, allowing us to piece together the history of the universe, is remarkable. The launch of the James Webb Space Telescope will give us some vastly improved infrared images, and will inevitably raise new questions to challenge future generations of scientists.![]()

- The author, Carole Haswell, is professor of astrophysics, The Open University

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence

Comments